Literary witnesses to the cultivation of music by the French kings of Cyprus are found in a variety of sources, but nearly all of the surviving music associated with the Lusignan court is contained in a single manuscript: Torino Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria J.II.9. This remarkable document was, according to Karl Kügle (2012), evidently copied between 1434 and 1436 under the supervision of Jean Hanelle, one of two priest-musicians from Cambrai (the other was Gilet Velut) who arrived in Cyprus in 1411 with Charlotte of Bourbon, the second wife of King Janus I (1398–1432). Whereas Velut appears to have soon left the island, Hanelle remained in the service of the Lusignan family for decades, becoming scribendaria of the Roman Catholic cathedral of Nicosia in 1428 and also, at some point, master of the Cypriot king’s chapel. Probably travelling to Italy in 1433 as part of the Cypriot delegation for the marriage of Anne of Lusignan to Louis of Savoy, Hanelle then seems to have supervised the production of Torino J.II.9 for the Avogadro family of Brescia, whose coat of arms is on the first folio of the codex.

Literary witnesses to the cultivation of music by the French kings of Cyprus are found in a variety of sources, but nearly all of the surviving music associated with the Lusignan court is contained in a single manuscript: Torino Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria J.II.9. This remarkable document was, according to Karl Kügle (2012), evidently copied between 1434 and 1436 under the supervision of Jean Hanelle, one of two priest-musicians from Cambrai (the other was Gilet Velut) who arrived in Cyprus in 1411 with Charlotte of Bourbon, the second wife of King Janus I (1398–1432). Whereas Velut appears to have soon left the island, Hanelle remained in the service of the Lusignan family for decades, becoming scribendaria of the Roman Catholic cathedral of Nicosia in 1428 and also, at some point, master of the Cypriot king’s chapel. Probably travelling to Italy in 1433 as part of the Cypriot delegation for the marriage of Anne of Lusignan to Louis of Savoy, Hanelle then seems to have supervised the production of Torino J.II.9 for the Avogadro family of Brescia, whose coat of arms is on the first folio of the codex.

Since all of the music in J.II.9 is anonymous and there are no known melodic concordances with other sources, Kügle has suggested that its contents may be largely the work of Hanelle, and, perhaps, of some of his colleagues at the Lusignan court. The Torino manuscript opens with a section of Latin plainchant (a rhymed Office and Mass for St Hilarion, a rhymed Office for St Anne, and six sets of chants for the ordinary of the Mass), followed by a fascicle of polyphonic music for the Mass ordinary, and then another section containing 41 polytextual motets (33 in Latin and 4 in French). The remainder of the codex is devoted almost entirely to polyphonic French secular song (ballades, virelais, and rondeaux), the exception being a single polyphonic Mass cycle inserted by a later hand after the fascicle of ballades. The polyphony of J.II.9 ranges in idiom from technically advanced compositions displaying the rhythmic complexity characteristic of the so-called ars subtilior (‘subtler art’) cultivated in France and northern Italy during the later fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries to works in comparatively simple styles. An example of the latter is the largely homophonic Gloria in excelsis 10 for three voices, which features textures not entirely unlike those that could be produced by polyphonically elaborating chant in performance (as in the preceding Kyrie for St Hilarion).

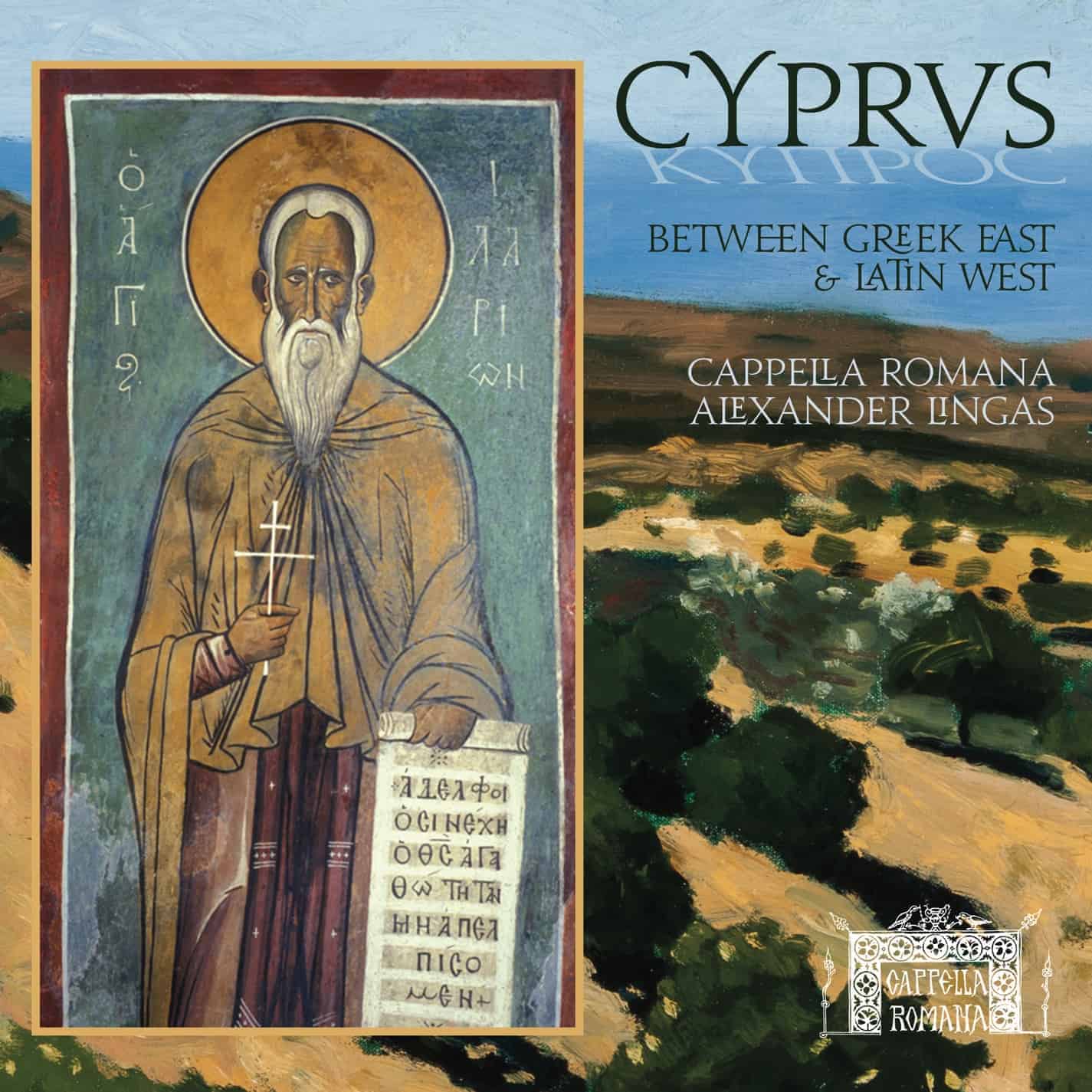

Interspersed throughout the present recording is music for St Hilarion, an early Christian monk whose biography was written by St Jerome. Born in Gaza in 291, he learned asceticism in Egypt as a disciple of St Anthony the Great and completed his earthly life as a hermit near the city of Paphos in Cyprus. St Hilarion was thereafter regarded as a patron of the island; the castle in Kyrenia that served as the Lusignan summer residence was dedicated to him. In 1414 the court of King Janus marked the feast of St Hilarion (21 October) with newly composed services that the Avignon Pope John XXIII had recently approved for celebration with the issuance of a papal bull that is copied at the very beginning of codex J.II.9.

The Vespers responsory Letare Ciprus mixes praise for St Hilarion with supplication for the island, themes that the verse of the Mass Alleluia Ave Sancte Ylarion recalls amidst a stream of Greek terms. Detailed references to the life of the saint enrich the encomia and entreaties of the following Sequence Exultantes collaudemus in a manner similar to the texts of Motet 17 Magni patris/Ovent Cyprus, one voice of which, the motetus, directly asks Hilarion to intercede for King Janus.

The Vespers responsory Letare Ciprus mixes praise for St Hilarion with supplication for the island, themes that the verse of the Mass Alleluia Ave Sancte Ylarion recalls amidst a stream of Greek terms. Detailed references to the life of the saint enrich the encomia and entreaties of the following Sequence Exultantes collaudemus in a manner similar to the texts of Motet 17 Magni patris/Ovent Cyprus, one voice of which, the motetus, directly asks Hilarion to intercede for King Janus.

The medieval motet is a form of polyphony in which upper voices, each of which may be provided with its own text, are supported by a foundational part (the ‘tenor’) that is either taken from a pre-existing melody (often a piece of plainchant) or, as is the case with all but two of the motets in the Torino manuscript, newly composed. Nearly all of the parts in the motets of J.II.9 feature what modern scholars call ‘isorhythm’, namely the repetition of a rhythmic pattern (talea) one or more times following its initial statement. This repetition may be literal or, as in the case of Motet 8 Gemma Florens/Hec est dies, involve patterns of diminution (in this case, a talea repeated twice in 3:1 diminution for a total of four statements).

Gemma Florens/Hec est dies is one of several motets commemorating milestones in the life of the Lusignan family, evidently having been written to mark the baptism in 1418 of John, the son of Janus and Charlotte of Bourbon. Its triplum voice emphasises kinship with the French royal family into which Charlotte was born, mentioning a ‘Macarius’ who is probably to be understood as being St Denys of Paris. Its motetus, on the other hand, speaks of the birth of John the Baptist to Elizabeth before invoking Christ’s protection on King Janus. Although differing in their wording, both upper voices of Motet 33 Da magne Pater/Donis affatim are hymns of praise to God featuring the acrostic ‘Deo gratias’, the concluding response for the Mass of the Roman rite.

—Alexander Lingas

Read Part One

Read Part Two

Read Part Four

Concert Tickets

[one_half]

Seattle

Friday, 13 Nov. 2015, 7:30pm

Blessed Sacrament

TICKETS

[/one_half][one_half_last]

Portland

Saturday, 14 Nov. 2015, 7:30pm

Trinity Episcopal Cathedral

TICKETS

Sunday, 15 Nov. 2015, 2:30pm

St. Mary’s Cathedral

TICKETS

[/one_half_last]

You must be logged in to post a comment.