In his magisterial The Rise of European Music, 1380–1500, Reinhard Strohm traces the development and dissemination of complex styles of music written with multiple voice parts using measured (‘mensural’) notation that enabled precise rhythmic coordination of the voices. By the middle of the fifteenth century the most notable centers for the production of this polyphonic (‘many voiced’) music were religious establishments in the cities and courts of northwestern Europe that trained singer-composers such as Guillaume Dufay (ca. 1397–1474), Johannes Ockeghem (ca. 1410–ca. 1497), Jacob Obrecht (ca. 1457–1505), Josquin Desprez (ca. 1450–1521), and Adrian Willaert (ca. 1490–1562) who took up influential musical posts elsewhere and thus assured that polyphony became a pan-European style of art music. Subsequent generations of composers of polyphonic music modified the style in various ways, on the one hand refining and systematizing its techniques of combining independent voices in counterpoint, and on the other responding to classicising trends in Renaissance humanist thought regarding the proper setting of text.

In his magisterial The Rise of European Music, 1380–1500, Reinhard Strohm traces the development and dissemination of complex styles of music written with multiple voice parts using measured (‘mensural’) notation that enabled precise rhythmic coordination of the voices. By the middle of the fifteenth century the most notable centers for the production of this polyphonic (‘many voiced’) music were religious establishments in the cities and courts of northwestern Europe that trained singer-composers such as Guillaume Dufay (ca. 1397–1474), Johannes Ockeghem (ca. 1410–ca. 1497), Jacob Obrecht (ca. 1457–1505), Josquin Desprez (ca. 1450–1521), and Adrian Willaert (ca. 1490–1562) who took up influential musical posts elsewhere and thus assured that polyphony became a pan-European style of art music. Subsequent generations of composers of polyphonic music modified the style in various ways, on the one hand refining and systematizing its techniques of combining independent voices in counterpoint, and on the other responding to classicising trends in Renaissance humanist thought regarding the proper setting of text.

Codified for subsequent generations in the music theory of Gioseffo Zarlino (1517–1590) and the works of composers including Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (ca. 1525–1594), Orlande de Lassus (ca. 1530–1594), and Tomás Luis da Victoria (1548–1611), the resulting synthesis has continued to echo through the centuries. At the dawn of the seventeenth century Claudio Monteverdi enshrined the High Renaissance style of polyphony as the ‘First Practice’ of music, an appellation that within a few decades had been changed to the ‘Stile antico’. Composers working through the nineteenth century continued to draw selectively on the ‘Old Style’ in their vocal and instrumental works, even as a few pieces by actual Renaissance composers persisted in the repertories of church choirs.

Interest in the full inheritance of Renaissance polyphony awakened in the later nineteenth century thanks to nationalist and revivalist movements across Europe, the most prominent being the Caecilian Movement amongst Catholic Germans to revive chant and the music of Palestrina. Coinciding with the rise of academic musicology, these movements sought to recover the heritage of musical pasts that were seen as offering forms of expression that were somehow purer than the Italian styles of operatic and instrumental music that had become internationally dominant in Western Art Music during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As a result vast quantities of early polyphony were studied and published, thereby laying the foundations of the modern Early Music movement.

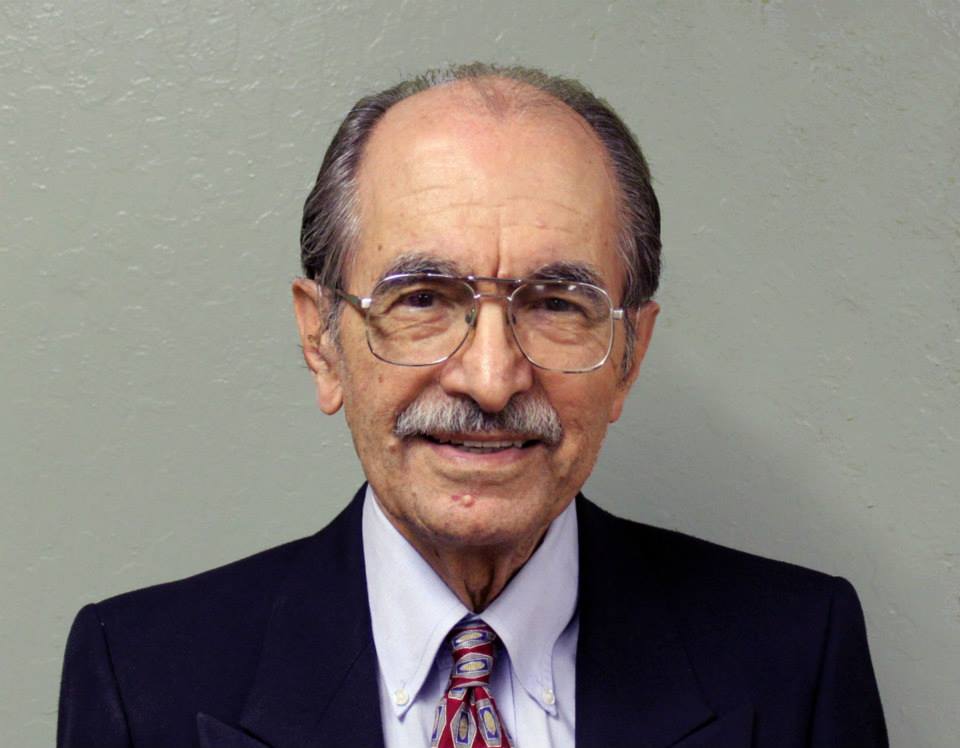

Although this search for musical roots and the revival of early repertories that it engendered strongly influenced the course of sacred music in late Tsarist Russia through the work of the Moscow Synodal School, only sporadically has it affected the composition of Greek Orthodox liturgical music. After the Second World War in California, however, a group of young Greek American composers began to set Byzantine chants for mixed chorus using the techniques of polyphony they had encountered in their universities and in American concert life. Three of these composers received their doctorates from the University of Southern California: Frank Desby (1922–92), for much of his life Director of Music at St Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral; Peter Michaelides (b. 1930), who later continued his academic career in the Midwest; and Tikey Zes (b. 1927), whose contributions both to Early Music and Greek Orthodox liturgical music are being honoured in these concerts.

Although this search for musical roots and the revival of early repertories that it engendered strongly influenced the course of sacred music in late Tsarist Russia through the work of the Moscow Synodal School, only sporadically has it affected the composition of Greek Orthodox liturgical music. After the Second World War in California, however, a group of young Greek American composers began to set Byzantine chants for mixed chorus using the techniques of polyphony they had encountered in their universities and in American concert life. Three of these composers received their doctorates from the University of Southern California: Frank Desby (1922–92), for much of his life Director of Music at St Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral; Peter Michaelides (b. 1930), who later continued his academic career in the Midwest; and Tikey Zes (b. 1927), whose contributions both to Early Music and Greek Orthodox liturgical music are being honoured in these concerts.

Following a move to the San Francisco Bay Area, Dr Zes made a pair of LP recordings for the Lyrichord label in the 1960s representing his parallel work in these fields. With the choir of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Ascension in Oakland, where he was then director of music, he recorded an album of Greek Orthodox liturgical music dominated by his own choral settings for mixed voices and organ. For the other album he directed the Berkeley Chamber Singers in a landmark recording of two settings of the ordinary of the Roman mass by Johannes Ockeghem, a composer who for much of his life served the royal family of France: the Missa Fors seulement, which is based upon the tenor of the composer’s own setting of the secular song Fors seulement, and the Missa My my.

The designation ‘My my’ is attached to the mass in the Chigi Codex (Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Chigi C VIII 234) and, according to Ross Duffin, appears to refer to the piece being in one of the Phrygian modes (based on the note E=’mi’ in solfège). The mass shows a musical relationship to the composer’s setting of the virelai (a form of secular song) Presque transi. Gayle C. Kirkwood has furthermore suggested that a form of theological allegory may be encoded in the mass, whereby the citations of the song and the recurrence of the musical interval of a fifth could have been read by the clerics of St Martin of Tours, where Ockeghem for many years was attached as treasurer, as referring to the Passion of Christ. At all events, the Missa My my is a work of polyphonic mastery that shows in the sophisticated development of its musical lines the skill that Josquin later eulogized in his Déploration on the death of Ockeghem. On the present programme we offer four of the five movements of this mass alongside seasonal works by three composers of the late Renaissance that Dr Zes has cited as influential on his own development: Palestrina, Victoria and Lassus.

The Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom (1991/96)

The Divine Liturgy bearing the name of St John Chrysostom (d. 407) is the form of the Eucharist celebrated most frequently in the modern Byzantine rite. Like the communion services of most other Christian traditions, it features two large sections: a service of the Word that climaxes with readings from the New Testament and concludes with the dismissal of those preparing for baptism (the catechumens); and a service of the already initiated Faithful during which the Gifts of Bread and Wine are brought to the altar and offered in a great prayer of thanksgiving (the Eucharistic Prayer or anaphora) before being distributed as the Body and Blood of Christ in Holy Communion. In common with the Roman mass, the Byzantine Divine Liturgy also contains both invariable (ordinary) and variable (proper) chants.

Dr Zes has written several choral settings in Greek and English of the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, the first of which was published in 1978. He completed the setting featured on the second half of our concert in 1991, leading to its concert premiere the following year by Cappella Romana, to which he later dedicated an expanded edition of the work in 1996. It is a collection of choral settings intended for Orthodox liturgical use and, like many other such publications (for example, Tchaikovsky’s All-Night Vigil, op. 52), includes more music than would ever be required for a single service. For the present concert performances we offer excerpts from a normal Sunday celebration of the Liturgy by a single priest, a service that without abbreviation would last between ninety minutes and two hours.

Although Dr Zes’s 1996 Liturgy often echoes Byzantine chant in Modes 1, Plagal 1 and, less often, Plagal 4, the vast majority of its melodies are original. Musical unity is provided instead through such formal devices as the recurrence of invertible counterpoint—that is, the switching of melodies among the voice parts—in the antiphons, Trisagion and Communion Verse. Despite the paucity of recognisable chants, the 1996 Liturgy bears the marks of a composer long engaged with the traditions of Orthodox worship. Choral responses uttered in musical dialogue with the celebrant are, in keeping with their liturgical function, generally short, homophonic and unaccompanied. Only at liturgically or textually significant points does the musical texture thicken as parts multiply in passages of homophonic declamation or dense counterpoint (examples of the latter may be heard in the musical evocations of angelic worship of the Trisagion, Cherubic Hymn, Sanctus (‘Holy, Holy, Holy’), Megalynarion and Communion Verse). Cumulatively opulent in its variety, level of difficulty and ecstatic polyphonic climaxes, this Liturgy achieves a balance of splendour with restraint that is, its echoes of the Renaissance notwithstanding, thoroughly Byzantine.

[one_half]

Seattle

Friday, 9 January 2015, 8:00pm

St. Joseph’s Parish

[/one_half][one_half_last]

Portland

Saturday, 10 January 2015, 8:00pm

Trinity Episcopal Cathedral

Sunday, 11 January 2015, 2:00pm

St. Mary’s Cathedral

[/one_half_last]

You must be logged in to post a comment.