Vasily Polikarpovich Titov (c.1650–c.1715) – Cherubic Hymn; Megalynarion

Vasily Titov was one of two leading composers of Russian Baroque music, the other being Nikolai Diletsky (c. 1630–80). Titov’s life and work mark the mid-point of the process of Russia’s musical Westernization, which gained new momentum during the reign of Tsar Peter the Great (1689 –1725).

In order to create a Baroque style appropriate for Church Slavonic, Titov fused the prosody of Slavonic with Western European compositional techniques: from simple German harmonizations to extravagant polyphonic and cori spezzati (“separated choirs”) effects made famous by Monteverdi and Schütz. Titov was a prolific composer, having written at least 200 vocal works while singing and working in Moscow.

The two selections in this program—the Cherubic Hymn, during which the bread and wine to be sanctified are carried in procession before the Eucharistic prayer begins, and the Marian hymn “It is truly right,” sung at the close of the Eucharistic prayer—are both from the ordinary of the Orthodox Divine Liturgy. However, these settings appear in one of Titov’s Divine Service collections marked “реквириальная” (“Requiem”), presumably to be used during memorial occasions.

Both feature eight-part writing with each section divided in two (two parts each for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass). Both employ Baroque call-and-response forms—high vs low voices or solos vs large ensemble—with echo and contrapuntal effects variously distributed among the eight parts.

Dmitry Stepanovich Bortniansky (1751–1825) – Concerto: “Come, O people, let us praise in song”

Dmitry Bortniansky was born in Ukraine but spent most of his life and career working for the Imperial Court Chapel in St. Petersburg. Initially a choirboy in the chapel, he studied with its director, the Italian Baldassare Galuppi, who also served as director of music at the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. As an adult, having succeeded Galuppi as the director of the Imperial Court Chapel, Bortniansky was a prolific composer for the Court in all genres, including operas in Italian and French, symphonic and chamber music, and art songs, as well as service music for the Russian Orthodox Church.

Bortniansky is known especially for his many settings of choral “concertos,” a cappella works that usually feature seasonal psalm or hymn texts to be sung during communion of the Divine Liturgy following the prescribed psalmody. A contemporary of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, Bortniansky transfers elements of galant and classical instrumental forms to a cappella choir with hints of romanticism. This concerto in the triumphant key of D major is set in three “movements,” following a typical late Baroque or Classical model, with an opening “Allegro maestoso” (Quick, majestically) in 4-beat time, followed by an “Adagio” (Slow) in triple time, then closing with an “Allegro moderato” (Moderately quick) returning to 4-beat time.

This form allows for extensive word painting: colorful musical treatments to reflect the meaning of each phrase of text. For example, the middle movement on the text “O Thou who wast crucified and buried” is set to slow somber music in the relative key of B minor, followed by ascending melodic phrases on the text “and art risen” in the piece’s original, major key.

Throughout, solo voices are starkly contrasted with the “ripieno” (It., “stuffing,” the full ensemble) much as an instrumental concerto grosso posits a group of soloists—the concertino—against the full orchestra, the ripienists.

—Mark Powell

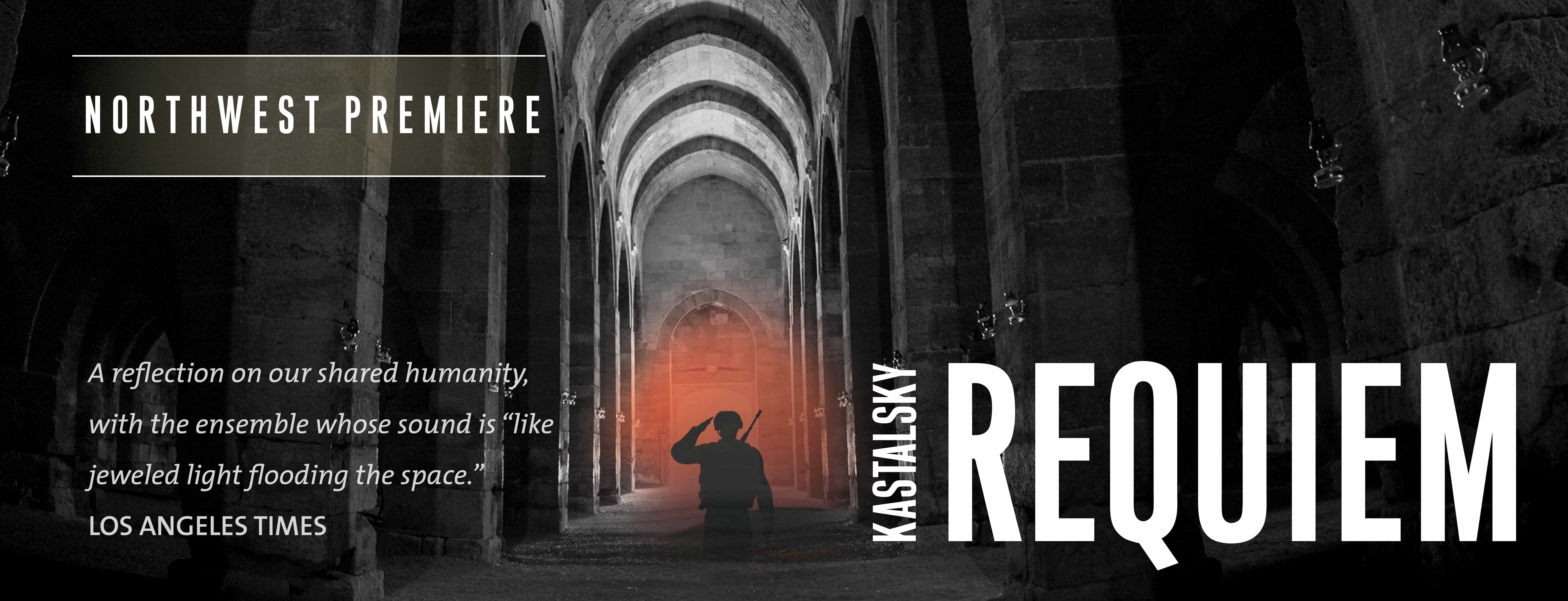

Alexander Kastalsky (1856–1926) – Requiem: “Vechnaya Pamiat Geroyam” (“Memory Eternal to the Fallen Heroes”)

In the autumn of 2018, the world commemorated the centennial of the Armistice to one of the largest military conflagrations in the history of mankind. The First World War, once referred to as “the war to end all wars,” saw the mobilization of nearly 70 million military personnel worldwide, from Europeans to Asians to Americans, and resulted in 16 million casualties, both military and civilian.

Often viewed as the end of the old European order and the commencement of the modern era, the war brought about the demise of the Austro-Hungarian, German, Russian, and Ottoman Empires; it also left in its wake a number of unresolved geopolitical issues that, 21 years later, led to the outbreak of the Second World War. In the face of the war’s devastation, the Russian composer Alexander Kastalsky conceived the idea of a musical “service of remembrance for soldiers who have fallen for the common cause.”

Kastalsky was a seminal figure upon the national musical landscape of Russia in the first two decades of the 20th century. A student of Tchaikovsky and Taneyev, he was appointed to the faculty of the Moscow Synodal School of Church Singing in 1887 and remained affiliated with that institution until it was closed in 1918 by the Bolsheviks. As a composer, conductor, folklorist, and administrator, by nature inquisitive and innovative, he moved freely among the spheres of church, classical, and folk music in a way very much his own. In his time, he was acclaimed as the founder of a new, truly national Russian style of church music, in which melodies and individual chant formulas of Znamenny—the earliest notated chant known among the Eastern Slavs—and other ecclesiastical chants are combined with techniques of counter-voice polyphony drawn from the Russian choral folk song. The skillful use of these peculiarly Russian elements give Kastalsky’s works a marked national flavor, while the use of church melodies links them to centuries-old traditions of the Eastern Orthodox liturgical aesthetic. His compositional techniques were emulated and developed by a host of composers, including Pavel and Alexander Chesnokov, Alexander Grechaninov, Viktor Kalinnikov, Alexander Nikolsky, Konstantin Shvedov, Nikolai Tcherepnin, and Sergey Rachmaninov: the latter would send pages of his manuscripts to Kastalsky for comment and approval.

Kastalsky’s compositional output was largely limited to miniature forms—sacred choruses, some 175 of them, and choral folk song arrangements. However, at the height of his musical career, in response to the unfolding events of the First World War, Kastalsky undertook to compose a large-scale Requiem that would follow the general plan of the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass but would use musical themes from the Latin rite, the Anglican rite, and the Orthodox Panihida (or memorial service), both in its Serbian and Russian Orthodox variants. By late 1915, the initial version of the score, entitled Bratskoye pominoveniye (“The Fraternal Commemoration”) was laid out in twelve movements for chorus and organ. But the composer soon realized that he would likely encounter objections from Russian Orthodox authorities both to the use of the organ and to the idea of combining texts and liturgical elements from both Orthodox and non-Orthodox sources. Thus, he discarded the idea of a trans-confessional liturgical service in favor of a choral-orchestral work for the concert stage. This version was completed in late 1916, and the premiere took place on 7 January 1917, in Petrograd.

But even as the choral-instrumental versions of Kastalsky’s Requiem evolved from a liturgical observance to a concert work, the composer still retained the thought of creating an a cappella version that could be sung in Russian Orthodox churches and concerts of sacred music. In early 1916, he reworked three movements from the choral-organ version for unaccompanied chorus, which were premiered by the Moscow Synodal Choir on 6 March 1916. After their success, he continued in the same vein, completing the a cappella version in late 1916; the score was published in early 1917, bearing the title Vechnaya Pamiat Geroyam: Izbrannïye pesnopeniya iz panihidï (“Memory Eternal to the Fallen Heroes: Selected Hymns from the Memorial Service”).

Memory Eternal follows the basic structure of the typical Orthodox Panihida. However, reflecting the earlier incarnations of the work as an inter-confessional concert piece, the composer omits certain prescribed hymns and changes the order in some places.

The Great Litany begins the memorial service with a prayer for the entire world and for those who have departed this life. Petitions intoned by the deacon, who in the Orthodox realm functions as a liturgical worship leader, are answered by the choir, using at various times the Greek and Church Slavonic renditions of the response “Lord, have mercy.”

In the Panihida service, the initial Litany segues into an Alleluia, followed by a Troparion and Theotokion—brief hymns that contain the essence of the feast or occasion being commemorated; in this instance, the theme is the Creator’s unceasing providence for the living and the departed who place their hope in Him. In contrast to Western practice, the Orthodox do not suspend the singing of “Alleluia” during periods of fasting and mourning, but rather reaffirm the “joyful sadness” that accompanies both the ascetic practices of Lent and the passing of a faithful soul from earthly life into eternity.

Kastalsky omits the next major set of hymns of the Panihida, the Troparia evlogitaria—verses interspersed with the refrain Blessed art Thou, O Lord, teach me Thy statutes—and proceeds to the hymn Give rest, O our Savior. Rather than quoting a pre-existing chant melody, the composer employs Znamenny chant motives as building blocks that migrate from voice to voice—a device he pioneered in many of his shorter compositions. The gentle rocking movement in the accompanying voices recalls the fifth movement, Nïne opushchaeshi (“Nunc Dimittis”), from Rachmaninov’s All-Night Vigil, composed approximately a year earlier.

In Orthodox belief, those departed from the earthly life are regarded as being asleep, awaiting the universal resurrection at the end of time. One of the most touching and memorable portions of the Orthodox funeral are the refrains Pokoy, Ghospodi, dushï usopshïh rab Tvoih (“Give, rest, O Lord, to the souls of Thy servants, who have fallen asleep”), which are sung a number of times alternately between the choir and the clergy. Kastalsky sets this refrain as a lullaby, using a 6/8 metre that is not typically heard in Russian Orthodox church music.

The following movement, Molitvu proliyu (“I will pour out my prayer”), was newly composed for the unaccompanied Russian Orthodox version. The soloistic arioso of the first tenors, sung over the sustained accompaniment of the chorus, makes this the most dramatic and tortured of all the movements, perhaps reflecting the more than two years of a difficult war that had ensued since the composer first began work on the Requiem in the summer of 1914.

The Kontakion, So sviatïmi upokoy (“With the saints give rest”) and its Oikos, Sam yedin yesi Bezsmertnïy (“Thou alone art immortal”), are built upon well-known Kievan and Znamenny chants. In the original choral-instrumental version patterned after the Latin Requiem Mass these two movements were used as the opening Requiem aeternam and Rex tremendae, respectively; this accounts for the appearance in measure 28 of the striking Dies irae Gregorian chant motif, which has no counterpart in the Orthodox memorial service.

Tï yesi Bog, soshedïy vo ad (“Thou art God, who descended into Hades”) was originally the Confutatis movement of the choral-orchestral version, which accounts for its fiery and tumultuous opening and jagged bass line in the opening section. While both the Latin and Slavonic texts speak of Hades, in Orthodox iconography (and theology) the resurrection of Christ is always depicted as “the harrowing of Hell,” in which Jesus is shown standing upon the broken gates of Hades and extricating Adam and Eve, together with all the righteous Old Testament patriarchs and saints, from its bonds.

In the choral-orchestral version, the music of Upokoy, Bozhe (“Give rest, O Lord”) was used for the Agnus Dei, which has no Orthodox counterpart. In its place, Kastalsky uses one of the Troparia evlogitaria omitted earlier; this is the one instance in which the composer deviates from the order of the Panihida service. The melody is of Serbian Orthodox origin, echoing several other works in which Kastalsky arranged these graceful and tuneful chant melodies.

In the tenth movement the composer refashions a series of call-and-response fanfares between instruments and choir of the choral-orchestral version into the responses of the Triple Litany—so called because of the three-fold Ghospodi, pomiluy (“Lord, have mercy”) refrain that answers the deacon’s prayerful petitions for the departed.

The work concludes with Vechnaya pamiat (“Memory Eternal”), a prayer that asks for the departed to be remembered by God forever. As the Russian theologian Fr. Pavel Florensky explains: “‘To be remembered’ by the Lord is the same thing as ‘to be in Paradise.’ ‘To be in Paradise’ is to be in eternal memory and, consequently, to have eternal existence.” The Serbian chant melody used as the theme preserves the multi-national character of the piece to the end.

—Vladimir Morosan (www.musicarussica.com)

From the program note in the recording of this work by the Clarion Choir, available at this concert.

PROGRAM

- Vasily Titov (c.1650–c.1715)

- Cherubic Hymn

It is truly right / Достойно есть

- Cherubic Hymn

- Dmitri Bortniansky (1751–1825)

- Concerto No. 15 “Come, O people, let us praise in song”

- Soloists: Catherine van der Salm, Photini Downie Robinson, Kristen Buhler, Susan Hale, Daniel Burnett, Scott Graff, David Stutz

- Concerto No. 15 “Come, O people, let us praise in song”

- Alexander Kastalsky (1856–1926)

- Memory Eternal to the Fallen Heroes

I. Great Litany / Ектения Векикая

John Michael Boyer, deacon; Daniel Burnett, priest

II. Alleluia and With profound wisdom / Аллилуия и Глубиною мудрости

Scott Graff, soloist

III. Give rest, O our Savior / Покой, Спасе

IV. Give rest, O Lord / Покой, Господи

V. I will pour out my prayer / Молитву пролию

VI. With the saints give rest / Со Святыми упокой

VII. Thou alone art immortal / Сам Един еси Безсмертный

VIII. Thou art God, who descended into Hades / Ты еси Бог, сошедый во ад

IX. Give rest, O Lord / Упокой, Боже

X. Triple Litany / Тройная ектения

John Michael Boyer, deacon

XI. Memory Eternal / Вечная память

- Memory Eternal to the Fallen Heroes

You must be logged in to post a comment.