Requiem for the Forgotten, Cantus Missae

Program Notes by Mark Powell and Frank La Rocca

Josef Rheinberger: Cantus Missae in E-flat major, Op. 109

SEATTLE

Friday, March 28 @ 7:30pm

St. James Cathedral

PORTLAND

Saturday, March 29 @ 2:00pm

St. Mary’s Cathedral

LAKE OSWEGO

Sunday, March 30 @ 3pm

Our Lady of the Lake Parish

Josef Gabriel Rheinberger (1839–1901) was born in Liechtenstein, later spending most of his life in Bavaria, there solidifying his reputation as a brilliant composer and organist and serving as court conductor in Munich, where he oversaw music at the Royal Chapel. Rheinberger was, as he is today, particularly known for his sacred music: vocal works including masses, motets, and a delightful Christmas cantata Der Stern von Bethlehem (The Star of Bethlehem) and organ works. However, his vast output also included operas, symphonies, chamber music, and secular choral pieces.

Rheinberger’s Cantus Missae in E-flat Major, Op. 109 for double choir is one of his most celebrated choral works. Composed in 1878, this masterpiece demonstrates Rheinberger’s command of Renaissance and Baroque counterpoint and Romantic (that is, more chromatic) harmony, balancing the two to create a work of intense emotion and expressive beauty.

I was particularly pleased when our guest conductor Richard Sparks agreed to program this Rheinberger Mass with La Rocca’s Requiem for the Forgotten. I had the great pleasure to sing the Rheinberger with the combined forces of Chœur de Chambre de Namur (Belgium) and the Kammerchor Stuttgart (Germany) under the direction of Frieder Bernius early in my career in 1992. Dr. Sparks is taking the same approach to the diction of the Greek and Latin texts as Bernius does, applying to them received Germanic pronunciation.

At the time Rheinberger composed his Cantus Missae, church music in the Catholic tradition in Germany was undergoing a transformation. The reactionary Cecilian Movement in the mid-19th century aimed to restore sacred music to what its supporters saw as a more pure and reverent style, inspired by Renaissance polyphony and Gregorian chant. While well-intentioned, the movement ultimately became rigid in its rules, limiting artistic expression.

The reformers sought to move away from the orchestral and operatic styles (perceived to be influenced by Enlightenment philosophy) that had become common in church music. Think of the masses of Mozart and Haydn, “sweets of sin” to the taste of the reformers. The movement instead favored a cappella singing and a strict adherence to Renaissance-style polyphony and non-chromatic modal harmony. Composers and scholars rediscovered and promoted the works of Palestrina and other Renaissance masters, believing their style, along with Gregorian Chant, to be the ideal for sacred music.

History shows the musical results by composers in favor of the Cecelian Movement were at best uneven and at worst uninspired and tedious. The movement’s uncompromising approach led to opposition from those who wanted a more balanced integration of old and contemporary musical styles. Initially sympathetic to this movement, Rheinberger ultimately distanced himself from its strict limitations, allowing himself greater creative freedom in his sacred compositions. His Cantus Missae embodies this artistic liberation, blending rich harmonic language with structural clarity and spiritual depth.

The Mass throughout evokes the grandeur of earlier choral traditions, particularly the Venetian cori spezzati technique (literally “broken choirs”), where groups of singers sing in dialogue from separate locations, something maintained today more commonly in Orthodox Churches with right and left choirs. The two choirs are present from the start in the expansive Kyrie, in which one choir begins and a response comes from the other. The Gloria and Credo are notable for their clarity and conciseness, setting the text largely in a straightforward declamatory style. In the Credo, Rheinberger allows himself moments of vivid musical expression—so-called “text painting”—particularly at key points such as “et incarnatus est” (and was made incarnate), when the faithful devoutly genuflect. This also occurs when the music tenderly descends on the words addressing the suffering and burial of the Lord “passus et sepultus est,” and at “resurrexit” (resurrected), where the voices rise dramatically—all expressive techniques that the Cecilian movement would have discouraged. The Sanctus and Benedictus appropriately bring a more ethereal and timeless quality as a response to the Eucharistic prayer, while the Agnus Dei builds toward an extended and luminous “dona nobis pacem” (grant us peace), repeating the word “pacem” as its final gesture.

The inclusion of this Mass on this program goes well beyond its musical compatibility with Frank La Rocca’s Requiem for the Forgotten. Rheinberger dedicated his Cantus Missae to Pope Leo XIII (in office from 1878 to his death in 1903), best known for his commitment to social justice. His 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum addressed the harsh conditions of workers in the industrial age, condemning both unregulated capitalism and socialism. He advocated simultaneously for fair wages, the right to private property, and the formation of labor unions, laying the foundation for Catholic social teaching and inspiring future efforts in economic justice. He also promoted personal involvement in politics and social reform, urging governments to protect the poor and vulnerable.

Musically and liturgically, Rheinberger demonstrates here his ability to honor tradition while embracing artistic innovation. Through its dedication to a social reformer, his work also remembers those in our society who are forgotten, imploring at its close that the Lamb of God grant us peace. Peace.

—Mark Powell

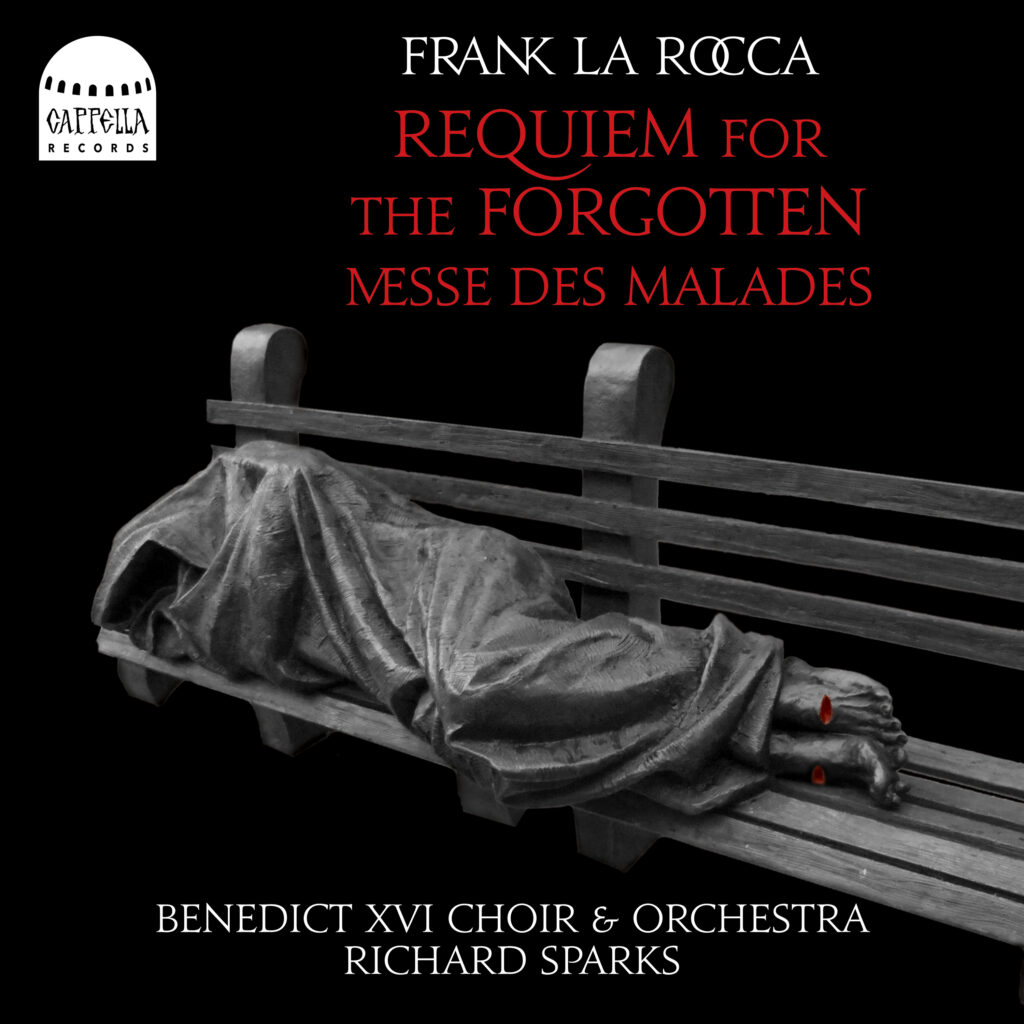

Frank La Rocca: Requiem for the Forgotten

Writing music for liturgy requires a composer to reconcile considerations that can appear to be in conflict. The music must, first, be reverent, and strive to bring glory to God. It must flow from a spirit of humility and simplicity. Unlike works purely for the concert stage, music for liturgy is not (or should not be) primarily a vehicle for the composer to project some “originality” of artistic vision. Such an approach can easily result in music for its own sake, rather than music that serves to deepen participation in the Liturgy through inner illumination of the texts. Finding that place where one’s own voice as a composer can join the voices of the past — as a fresh contribution to the great history of liturgical music — requires constant vigilance and introspection, especially in an age where originality is revered as the highest of all artistic aspirations. I have found this tension to be a potent source of creative inspiration.

Over the years I felt moved to link this essential aspect of the music to the subject reflected in Requiem for the Forgotten: the homeless, the refugee. Too often, we would rather not think about them, because doing so can elicit feelings that are discomforting. I could not escape such emotions when given the commission to write it by the Benedict XVI Institute. It entailed more than just forming a musical vision, but also coming to terms with what might be called an anthropology of these subjects. How are we linked to our fellow humans? Just what is our relationship to the unhoused person, to the refugee escaping war or political oppression?

The Requiem for the Forgotten (originally “for the Homeless”) had an arduous gestation period. I had very little frame of reference beyond a few people outside my grocery store to whom I would regularly give money. I had the same associations with Requiem Masses — the same, as I would imagine as most people’s: the Mozart, the Verdi, the Victoria. I could not reconcile these with the subjects I was now to compose for and about. Then I had a long talk about it one night with Dr. Thomas McLaughlin of San Francisco, the father of a young friend of mine. He told me about his many experiences treating the homeless in hospitals and he said to me, “You know, this is going to change you.” I realized in an instant I was resisting embracing the subject, much as I told myself otherwise. I also realized I had been coming about it from the wrong perspective.

I had been plagued by the thought that my music could not accomplish any tangible good for someone on the streets. Then it hit me: crafting policy to help homeless people on the streets is very important work, and so is the work of the artist. I came to realize, deep in my bones, that anything I could do must be grounded in something larger than a utilitarian calculus: it must rest ultimately in a special kind of faith, faith in the equal dignity of every human life. “Music not for their bodies, but for their souls” is the thought that came to me — it was, after all, a Requiem.

And so, the Introit has all the gravity and majesty one might expect for a “very important person” — because, seen from the perspective of their Creator, each of these souls is of completely equal dignity and worth to every other human person, regardless of their condition living on the streets. So too, for the refugee seeking haven from war or oppression: “…as long as you did it for one of these my least brethren, you did it for Me” (Matt. 25: 40).

This is not a Requiem based on the traditional pattern that Mozart, et al. had available to them. The contemporary Catholic “Rite of Christian Burial” does not include, for example, the “Dies Irae” — a great loss in my opinion. So, in the Kyrie — which features petitions on behalf of the homeless — I smuggled in the “Dies irae” Gregorian chant, setting the words “Kyrie, eleison” to the same notes as the chanted “dies irae, dies illa.

In “Christe, eleison” you can hear the chant for “solvet saeclum in favilla.”

The final tutti (all musicians) “Kyrie, eleison” finds these two chant phrases superimposed in counterpoint, “dies irae…” in the choral melody and “solvet saeclum…” in Viola I and organ.

A stirring poem by James Matthew Wilson, written especially for this composition, provides the text of “A Hymn for Ukraine,” which is sung by the choir alone. In this poem, Wilson pays tribute to a 20th-century hero of the Ukrainian people, the martyred priest Andrei Ischak of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church who, rather than abandon his parish, refused to escape approaching Red Army soldiers, saying “…the shepherd doesn’t abandon his flock. And I can’t leave my parishioners and conceal myself.” He was, instead, executed in 1941. He was beatified by Pope St. John Paul the Great in 2001. I set the poem somewhat in the manner of the telling of an old legend, a heroic tale for the children of future generations. I am the child of a Ukrainian mother whose parents fled the Bolsheviks in Ukraine, so I was deeply moved by Wilson’s magnificent poem and honored to include it in this Requiem (thereby expanding its scope and revising its title). With its refrain “This we bring you with our loss, for your altar and your cross,” it can be used at the Offertory in a liturgical setting.

The subject matter of this Requiem is certainly dark, but my piece is intended to do more than just underscore the tragedies that inspired it. Where there is God, there is hope. The text of “I will lift up mine eyes to the hills” is attributed to King David, either as a prayer before battle or as a pilgrim song — the “hills” being the city of Jerusalem. Either way, it is an expression of David’s confidence in his Lord’s justice and protection — a confidence that transcends temporal circumstances for any who place their faith in a good and just Creator.

With the Sanctus and Agnus Dei, we are brought back into the liturgical flow of the Mass. The Sanctus dwells in mystery and awe, while the Agnus Dei seems to be reaching out in anticipation of eternal rest, as it dwells on the final word “sempiternam” (always and forever). The concluding two phrases in the viola solo restate the opening choral phrases of the Introit, over the same pedal tone in organ and low strings, bringing a kind of closure to this Requiem — but not quite complete closure.

There remain the two final movements, as contrasting as any two adjacent movements could be, yet linked as a final commentary in this Requiem.

In “O Vos Omnes,” we hear the voice of the homeless and displaced refugees themselves, imploring those who “pass by” to see their suffering — and to see them as creatures made by God, possessed of immortal souls equal in dignity to any other person.

The text is from the Book of Lamentations 1: 12. Lamentations chronicles in excruciating detail the aftermath of the Fall of Jerusalem at the hands of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BCE. With the destruction of Solomon’s Temple the ancient Israelites lost — in one blow — their spiritual, political, and financial center of power, and were thrust into a state of profound doubt about their entire identity as the chosen people. The text moves from states of incredulity and grief to pleas for solace and expressions of remorse. I have tried to capture some of this volatile mix of emotions with a variety of devices: accusatory exclamations, dizzy/wandering chromatic movements, songful laments, and bitter major/minor polarities.

The Jews had to endure seventy years in exile before they were restored to their land, and so this piece does not attempt to bring the narrative to any kind of resolution at its end. Grief and loss linger in the quiet but unsettling final sonorities, captured by the wailing melody in the tenor solo on the words, “my pain.”

A tenor solo also begins the final movement, “Pie Jesu,” acting as a link between the two. Here the soloist pleads not to the surrounding populace, but to the Lord of mercy. He is joined by a companion alto soloist, and together they are brought into the full choral texture. The music speaks not of bitter despair, but rather of hopeful anticipation. And it comes to rest in the final “Amen” on the G-major harmony that was denied resolution at the end of “O Vos Omnes.” Requiem aeternam.

—Frank La Rocca

(Adapted by Mark Powell from the liner notes to the recording Requiem for the Forgotten / Messe des Malades)

You must be logged in to post a comment.