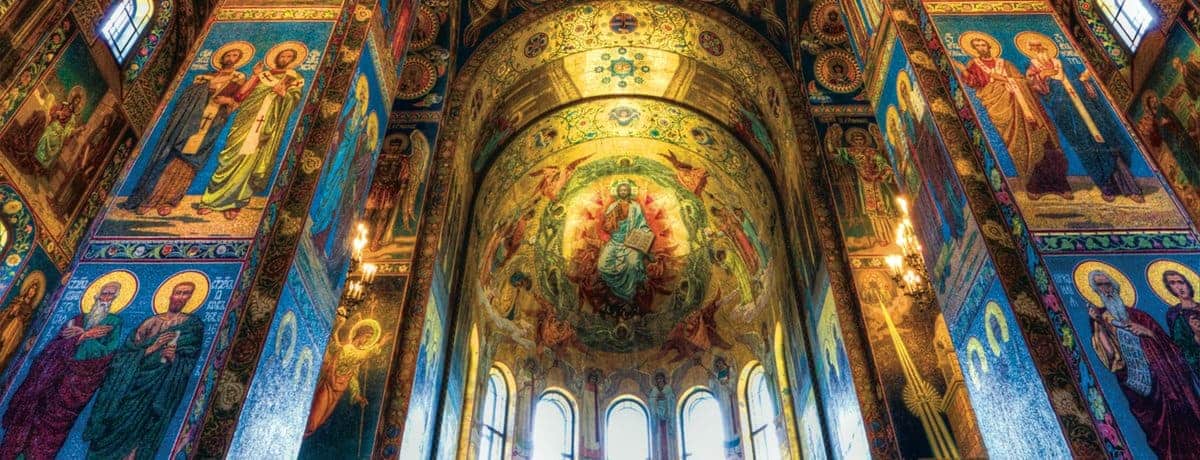

Major traditions of complex sacred music throughout Europe were shaped during the so-called “long nineteenth century” (the period of relative peace which lasted from the battle of Waterloo to the outbreak of World War I) by movements to recover elements of early traditions for modern use. These efforts, like contemporary “back-to-roots” endeavors in non-musical arts and the Romantic nationalisms to which they were all related ideologically, shared certain broad aims and methodologies even as they emphasized local particularities. Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants all employed the rapidly developing academic disciplines of liturgiology and musicology (both historical and comparative) to identify their historical, cultural, and spiritual roots. Scholarly findings were then harnessed to serve (re-) creative practice in ways that ranged from wholesale resurrections of neglected repertories to the composition of new music inspired by real or imagined pasts. e results in Western and Central Europe are well known: a musical spectrum from the Solesmes “restoration” of Gregorian chant to Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, in between which were revivals of Renaissance polyphony and Baroque liturgical music (especially that of J.S. Bach) that combined old and new in nearly equal measure.

This concert traces a quest that emerged out of the so-called “Russian Religious Renaissance” of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to renew the music of Russian Orthodoxy through the study and creative re-appropriation of its traditions of chanting. Two approaches to research were pursued simultaneously, in some cases by the same people: 1) the study of notated chant manuscripts and other historical documents reaching as far back as the Byzantine origins of Orthodox worship in medieval Rus’; and 2) the investigation of contemporary chanting in the worship of monasteries, Old Believers, southern Slavs, and Greeks. is research enabled antiquarian revivals in the form of concerts and published editions of historical works, as well as pastoral initiatives to promote the use of unison chanting. Yet scholarship arguably achieved its greatest impact by fostering the emergence of a “New Direction” in the creation of harmonized choral music for the Russian Orthodox Church, the crowning achievement of which is generally acknowledged to be the (mostly) chant-based All-Night Vigil, op. 37 of Sergei Rachmaninov (1873–1943).

Tickets

Seattle

Friday 31 March, 7:30pm

St. James Cathedral

Portland

Sunday 2 April, 3:00pm

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral

The stylistic indistinguishability of completely original sections of Rachmaninov’s Vigil from movements based on melodies from the Znamenny, Kievan, and Greek repertories of Russian chant points toward contradictions inherent in the New Direction. In pursuing a broad creative agenda that may be summarized as “back to the future,” its adherents forged inescapably modern syntheses through their (inevitably) selective use of data regarding historical and living traditions of Slavic and Byzantine chanting. Contemporary ideologies and perceptions of musical, spiritual, and/or ethnic purity governed the use of historical or ethnographic evidence, blurring lines between real and imagined traditions.

From the seventeenth century to the emergence of the New Direction in the later nineteenth century, there were three major streams of musical practice within Russian Orthodoxy:

- A group of chant repertories recorded in neumes or staff notation as a single melodic line. The oldest of these was Znamenny – from the word “znak” ([musical] “sign”) – chant, a repertory with Byzantine roots that was indigenized over the course of half a millennium. Out of the core Znamenny repertory emerged other bodies of chant, some of which were closely derivative regional variants (the most prominent

being Kievan chant), while others such as Demestvenny chant were created as supplements to adorn worship selectively with new (and o en elaborate) music. Post-medieval waves of musical influence from the Balkans led to the formation of additional Slavonic chant repertories labeled “Greek” and “Bulgarian.” - Multipart singing derived from the Slavic chant traditions listed above, most of it realized extemporaneously according to orally transmitted conventions, a practice known in western Europe as “chanting on the book.” The multipart textures that emerged from these polyphonic practices featured harmonic progressions, seventh chords, octave doublings, and parallel movements of vocal parts that are inadmissible according to Western textbooks of harmony and counterpoint. As Jopi Harri has recently shown, these practices undergird manuals for ordinary church singing (Obikhod) edited and published in multiple voice parts by three directors of the Imperial Capella in Saint Petersburg: Dmitry Bortnyansky (1751– 1825), Alexei Lvov (1798–1870), and Nikolai Bakmetev (1807–91).

- Singing music notated in multiple voice parts (partes) composed in the style of contemporary western European art music, albeit without the use of musical instruments. Renaissance and Baroque styles of partesny singing initially absorbed through Poland and Ukraine were replaced during the later eighteenth century by Galant and Classical works, a stylistic change stimulated by Catherine the Great’s appointment of Italian composers to head the Imperial Capella. Chants were occasionally harmonized using “textbook” western harmony and counterpoint, but most of the music composed in this style featured original melodic material.

The present concert surveys the progress of the New Direction in Russian church music through selections drawn mainly from three services: the All-Night Vigil, a composite of the offices of Vespers (evening prayer), Matins (morning prayer), and the First Hour celebrated on Saturday night and the eves of major feasts; the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, the ordinary form of the Eucharist in the Byzantine rite; and the Memorial Service (Panikhida). We represent the received practices of polyphonic chanting in nineteenth-century Russia with excerpts of collections recording the traditions of two great monastic foundations: the Monastery of the Kievan Caves (Kiev-Pechersk Lavra) as transcribed and arranged after its oral traditions of harmonization by Leonid Malashkin (1888); and the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra in Sergiev Possad near Moscow as edited by Hieromonk Nathaniel Bochkalo (1911). This style of chanting was ubiquitous and was found to be inspirational even by composers of the New Direction whose own church music rejected many of its harmonic devices. In some of his chant-based works, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) adopted the doubling of upper-voice melodies in bass voices, while Rachmaninov quoted the Kievan version of the morning hymn “Your Cross, O Savior” in his Second Piano Concerto.

One of the first composers to move toward the reorientation of Russian church music was Mikhail Glinka (1804–57), whose triumph with the nationalist opera A Life for the Tsar led to his appointment as Director of the Imperial Capella in 1837. During his brief tenure at court (1837–39), Glinka composed only a single sacred work (a Cherubic Hymn in a Romantic version of the imitative polyphonic style of the Renaissance) and apparently had little impact on the aesthetic trajectory of church singing. Late in life, however, Glinka returned to the composition of liturgical music a er a period of study in Berlin, where a setting of the Paschal hymn “Christ is Risen” is preserved among his papers. Having made the acquaintance of the abbot of the Coastal Monastery of St. Sergius near Saint Petersburg, (now Saint) Ignaty Brianchaninov, Glinka composed two works for the community: a set of responses to the Litany of Peace, and an arrangement for male voices of the Greek Chant melody of the responsory “Let My Prayer Be Set Forth” from the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. In both of these late works Glinka used a “strict style,” avoiding dissonance and chromatic alterations of the scale, that reflected his rejection of what he perceived to be the prevalence of Italian and German influence in contemporary Russian church singing.

The foundations for a broader quest to establish a distinctively Russian style of church music rooted in the past were strengthened in 1867 with the establishment of a department for the “History of Church Singing” at the Moscow Conservatory. Glinka’s late sacred works were nally published in 1878 by the Moscow rm of Jurgenson, which in that same year also released an original setting of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, op. 41 by Peter Tchaikovsky (1840–93). Tchaikovsky’s Liturgy immediately provoked litigation from Bakhmetev, who as Director of the Imperial Capella alleged that its unauthorized appearance contravened his powers of censorship over printed liturgical music. e dismissal of this lawsuit on a technicality in 1880 inaugurated a new era of productivity in Russian church music, out of which soon coalesced the creative re-imaginings of chant and folk music of the New Direction.

Tchaikovsky’s next publication of music for Orthodox worship was explicitly an attempt to reframe ancient traditions of Russian church singing: All-Night Vigil: An Essay in Harmonizing Liturgical Chants, op. 52 (1882). It was based almost entirely on melodies from major repertories of Russian chant, with harmonizations ranging stylistically from unmetered and modally pure settings in the “strict style” to relatively complex arrangements featuring counterpoint and other devices characteristic of Western art music. An example of the latter is the Polyeleos, a setting of a Greek Chant for festal matins that extends iterations of its refrain (“Alleluia”) with passages of imitative polyphony.

In 1883 Mily Balakirev (1836–1910) and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov were appointed co- directors of the Imperial Capella. Working with the assistance of a team of younger composers, Rimsky-Korsakov immediately set out to rework its core repertory of customary chants (Obikhod) according to academic principles of modal harmony and voice-leading. The results of this group e ort were published in 1887 as the All- Night Vigil based on Ancient Chants, from which we have excerpted its arrangements of Kievan melodies in Mode 1 for the Lamplighting Psalms and interpolated hymns (stichera) of Saturday vespers.

Composers in Saint Petersburg continued to recast ancient chants through 1923, when the Communist authorities prohibited the Petrograd People’s Choral Academy (as the Imperial Capella had been renamed) from performing Maximilian Steinberg’s recently completed Passion Week. (Passion Week received its world premiere by Cappella Romana 91 years later in 2014.) By that time leadership in Russian sacred music had long ago passed to composers and scholars based in the old capital of Moscow, a shift brought about in part by Tchaikovsky as a member of a committee that in 1886 completely reorganized the curriculum of the Moscow Synodal School of Church Singing. Newly hired conductor Vasily Orlov (1856–1907) quickly transformed its choir of men and boys into Russia’s leading vocal ensemble and a champion of new music, eventually including the most challenging sacred works of Rachmaninov and Alexander Grechaninov (1864–1956).

During the tenure of chant scholar and composer Stepan Smolensky (1848–1909) as its director (1889–1901), the Synodal School became the central hub of the New Direction, training and appointing as faculty composers including Alexander Kastalsky (1856–1926), Pavel Chesnokov (1874–1944), and Nikolai Tolstiakov (1883–1958). From the time of its reorganization the professional networks of the Synodal School faculty overlapped with those of the Moscow Conservatory, where Smolensky taught as a professor of the history of church music alongside colleagues including the composer-theorist Sergey Taneyev (1856– 1915). They later came to encompass scholars, performers, and composers of church music in Saint Petersburg, especially after Smolensky served a term (1901–1903) as director of the Imperial Capella.

Composers working during the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries within the orbits of the New Direction approached

the problem of formulating a chant-based style from a number of angles. In a treatise entitled A Theory of Ancient-Russian Church and Folk Singing on the Basis of Authentic Treatises and Acoustic Analysis (Moscow: 1880) the St-Petersburg-based theorist and composer Yuri Arnold (1811–98) began to expound a systematic approach to the modal harmonization of chants rooted in ancient theory that resembled contemporary work on Greek folk song and Byzantine chant by Louis-Albert Bourgault Ducoudray (1840–1910). Arnold’s approach was subsequently taken up by the priest, historian, and composer Dmitry Allemanov (1867–1928), who began to correspond with Smolensky in 1894 and taught the history of church singing at the Moscow Synodal School during the years 1910–18. Labeled “Greek Chant” in some of its republications, Allemanov’s setting of the matins antiphon “From My Youth” is an original composition in chant style. Allemanov, however, did compose numerous settings of authentic chants, mainly Russian but also Byzantine. The latter appeared in a pair of publications co-authored with Alexei Zverev that feature harmonized Byzantine melodies in Greek and Slavonic.

Sergey Taneyev was a master of academic styles of counterpoint whose major sacred works are two large-scale sacred cantatas for chorus and orchestra: John of Damascus, op. 1 (1883–84); and At the Reading of a Psalm, op. 36 (1912–15). He became interested in church music in the mid 1870s, discussing the matter with Tchaikovsky and occasionally venturing to produce his own settings of liturgical texts for unaccompanied chorus. Of Taneyev’s seventeen extant liturgical choruses, een are based on traditional Russian chants. Those for the All-Night Vigil were evidently intended, according to Plotnikova,

to be components of a cycle that, had it been completed, would have comparable to that of Tchaikovsky. Taneyev sets his chosen Znamenny, Kievan, and Greek chant melodies to various permutations of imitative polyphony or, as in the case of the Apolytikion of the Resurrection in Mode 1, homophonic writing in the “strict style”. Although never published during his lifetime, this Apolytikion is one of two chant-based works by Taneyev that the Synodal Choir performed in 1891 at Smolensky’s behest.

Ultimately, as Vladimir Morosan has noted, it was Smolensky and his assistant Kastalsky that succeeded in forging a distinctive and widely copied chant- and folk-related choral idiom that the former had christened “kontrapunktika.” Similar in texture to the nationalist style pioneered in secular music by Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881), kontrapunktika featured parallel vocal lines (including the fourths and hs forbidden by textbook harmony), constantly shi ing numbers of voices, drones, and irregular phrases based on chant melodies and their texts. Smolensky himself o ered only a small number of fully developed exemplars of this technique, the most extensive of which is the Panikhida on emes from Ancient Chants for Male-Voice Choir, a setting of the Russian Orthodox Memorial Service composed in 1904. Many of his other musical publications were editions of existing bodies of music, including a three-volume set of chant harmonizations arranged for male chorus that appeared in 1893, from which we perform the Prokeimenon for Saturday Vespers and a Cherubic Hymn for the Divine Liturgy.

After joining the Synodal School as a pianist on the recommendation of Tchaikovsky, Alexander Kastalsky rose through the ranks of its faculty to become director from 1910 to 1918. One of his most self-consciously antiquarian endeavors at the school was a performing edition of the medieval Russian version of the Service of the Furnace (1909). The Service had originated in the late Byzantine rite of Hagia Sophia as a quasi-dramatic retelling of the story of the Three Hebrew Youths in the fiery furnace from the Septuagint version of the biblical Book of Daniel. Previously recorded by Cappella Romana from manuscripts preserved today on Mount Sinai, the Greek prototype of the Service was celebrated during the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries between matins and the Divine Liturgy on the Sunday before Christmas in the cathedrals of Constantinople and Thessalonica. In Russia the Service expanded into a multi-day observance with spoken dialogue, additional chants, and pyrotechnics. Basing his work on recent scholarship, Kastalsky combined ancient chant sources with arrangement according to the techniques of kontrapunktika to create for the Moscow Synodal School a greatly abbreviated version lasting approximately thirty minutes. We sing its penultimate movement, a setting of verses from Psalm 136.

Nikolai Tolstiakov was a 1903 graduate of the Synodal School who served on its staff from 1907 through 1918 and then, like his mentor Kastalsky, for another five years during the institution’s twilight as a People’s Choral Academy. Tolstiakov originally published “Blessed is the Man,” an arrangement of Greek Chant melodies for selected verses of Psalms 1–3, as the second of five numbers for mixed chorus from the All-Night Vigil contained in his Opus 1. Like the paraliturgical choral concerto O Be Joyful in the Lord (Op. 19, No.2 of 1898) by Alexander Grechaninov, it was later arranged for male chorus by Pavel Chesnokov, another graduate turned staff member of the Synodal School. Grechaninov had acquired his association with the school when its choir premiered his Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, op. 13. According to Morosan and Rakhmanova, this led to conversations with faculty members who convinced him to adopt the techniques of kontrapunktika.

Svetlana Zvereva has documented how Kastalsky also exchanged ideas regarding stylistic directions in contemporary church music with Vladimir Glinkaov (1866–1920), a composer best known today for his piano works. In his All-Night Vigil, op. 44 (1911), a work premiered by the Synodal Choir and described by Kastalsky as “remarkable for the boldness of its exposition,” Rebikov went beyond the stylistic conventions of kontrapunktika to create his own soundworld of invented melodies and austere harmonizations. Rebikov’s music for vespers includes two solo chants in a quasi-Byzantine style: a setting of the Canticle of Symeon (the Nunc dimittis, Luke 2:29–32) for a tenor with a “mature timbre”; and a version of the Marian hymn “Hail, Virgin Mother of God” for a tenor with a “youthful timbre.”

The harmonically and sonically rich textures of Pavel Chesnokov’s mature choral style stand in polar opposition to the radical asceticism of Rebikov. Chesnokov began his career as a church composer by regularly employing traditional melodies, but over time turned toward original composition, preferring to suggest rather than to quote chant. This is the case with his second setting of the Russian Orthodox Memorial Service, the Panikhida No. 2, a work written for mixed voices as Opus 39 and then immediately adapted for male voices as Opus 39a (1913). In the Funeral Kontakion and Ode 9 of the Kanon, Chesnokov musically unifies a patchwork of textual fragments reflecting abbreviations commonly made to the service in late imperial Russia.

The dismantling of institutional infrastructure for the creation and performance of sacred music in the Soviet Union led the task of further development along the lines of the New Direction in the hands of Russian émigrés. Alexander Glazunov (1865–1936), who held the title of Director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory from 1905–1930, went abroad in 1928 on a concert tour from which he eventually decided not to return, settling in Paris in 1932. In the year before his death Glazunov composed his first known liturgical music for the choir of the St. Serge Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris, a pair of chant arrangements from the matins of Easter Sunday. The Paschal Exaposteilarion sets a Greek Chant melody with harmonies and counterpoint in the “strict style” that Morosan likens to the music of Rimsky-Korsakov and Taneyev.

Born in Saint Petersburg, Nikolai Kedrov, Jr. (1906–1981) was the son of Nikolai Kedrov, Sr. (1871–1940), a singer, composer of church music, and professor at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. After his family settled in Paris in 1923, the younger Nikolai resumed his musical training, eventually succeeding his father as director of the Kedrov Vocal Quartet. He was one of the editors of the so-called London Sbornik (1962–72), a multivolume collection of liturgical music that featured prominently both the composers of the New Direction and their émigré successors. Kedrov, Jr. contributed to this project many of his own arrangements of Russian chant, among which is his setting of the Greek Chant for the verses and refrains of Psalm 103, the opening psalm of Byzantine vespers.

Seattle

Friday 31 March, 7:30pm

St. James Cathedral

Portland

Sunday 2 April, 3:00pm

Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral

You must be logged in to post a comment.