In the year 637 AD the orthodox Christian Patriarch Sophronios (d. 638) surrendered Byzantine Jerusalem to the Arab Caliph Umar, inaugurating a period of Muslim rule in the Holy City that would last until its conquest by Latin Crusaders in 1099. Although subject to tribute, Jerusalem’s Christian inhabitants retained the right to continue celebrating both for themselves and for visiting pilgrims their distinctive forms of worship. These services made extensive use of the shrines associated with life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ that had been created with imperial patronage in the years that followed the official legitimation of Christianity by Roman Emperor Constantine I in 313.

In the year 637 AD the orthodox Christian Patriarch Sophronios (d. 638) surrendered Byzantine Jerusalem to the Arab Caliph Umar, inaugurating a period of Muslim rule in the Holy City that would last until its conquest by Latin Crusaders in 1099. Although subject to tribute, Jerusalem’s Christian inhabitants retained the right to continue celebrating both for themselves and for visiting pilgrims their distinctive forms of worship. These services made extensive use of the shrines associated with life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ that had been created with imperial patronage in the years that followed the official legitimation of Christianity by Roman Emperor Constantine I in 313.

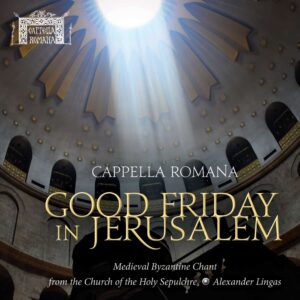

Constantine and his mother Helen had sponsored the most important of these edifices: the cathedral complex of the Holy Sepulchre built on the accepted site of Jesus’ crucifixion and entombment. Its major components were a large basilica (the Martyrium), an inner atrium incorporating the hill of Golgotha, the Rotunda of the Anastasis (Resurrection) over Christ’s tomb, and a baptistry. Egeria, a Spanish pilgrim of the late fourth century, describes in her diary how every week the clergy, monastics, and laity of late fourth-century Jerusalem would gather on Saturday evening and Sunday morning to remember the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus with readings, prayers, and psalmody performed at historically appropriate locations within the cathedral compound. These same events of sacred history were commemorated annually in a more elaborate fashion during Great and Holy Week, which climaxed with Easter Sunday (Pascha). Holy Week services in Jerusalem incorporated the buildings on Golgotha into a larger system of stational liturgy that made full use of the city’s sacred topography.

The musical repertories created for worship in the Holy City developed gradually over the centuries out of patterns of interaction between the secular (urban church) and monastic singers of Jerusalem and those of other ecclesiastical centres. Monks from the monastery founded by St Sabas (439–532) in the desert southeast of Jerusalem became active participants in worship at the Holy Sepulchre, which maintained a resident colony of ascetics later known as the spoudaioi. Responsorial and antiphonal settings of biblical psalms and canticles formed the base of cathedral and monastic liturgical repertories. Palestinian poet-singers subsequently increased the number, length, and musical complexity of the refrains sung between the biblical verses, leading by the sixth century (and possibly earlier) to the creation of hymnals organised according to a system of eight musical modes (the Octoechos). The contents of the earliest hymnbooks from Jerusalem are preserved today only in Armenian and Georgian translations.

Until the recent discovery of a few Greek sources for the urban rite of Jerusalem among the New Finds of the Holy Monastery of St Catherine on Mount Sinai, the most important surviving Greek witness to cathedral worship in the Holy City was the so-called Typikon of the Anastasis. Copied in 1122, this manuscript (Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem MS Hagios Stauros 43) contains services for the seasons of Lent and Easter as celebrated prior to the destruction of the Holy Sepulchre complex by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim in 1009 (and probably also, according to recent research (Galadza 2013), for many decades after its Byzantine reconstruction). Older and newer chants presented without musical notation coexist in the Typikon of the Anastasis. Thus works from the apogee of Christian Palestinian hymnody—a period initiated by the liturgical works of Sophronios and continued by the eighth-century poet-composers Andrew of Crete, John of Damascus and Kosmas the Melodist—are integrated with hymns by writers working within the traditions of the Constantinopolitan monastery of Stoudios. The latter had, at the behest of its abbot Theodore, adopted a variant of the monastic liturgy of St Sabas at the beginning of the ninth century. The resulting Stoudite synthesis of Palestinian and Constantinopolitan traditions was a crucial stage in the formation of the cycles of worship employed in the modern Byzantine rite.

The present recording features excerpts from the Service of the Holy Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ as it would have been celebrated in Jerusalem during the transitional period of its ritual Byzantinisation. An archaic cousin of the service celebrated in the modern Byzantine rite on Holy Thursday evening, this is a stational version of the office of early morning prayer (matins or orthros, literally ‘dawn’) in which eleven gospel readings narrate the events of the Passion of Jesus in a sequence beginning with his Last Discourse to his disciples (John 13:31–18:1) and ending with his burial (John 19:38–42). The texts and rubrics of the Typikon of the Anastasis form the basis of our reconstruction, supplemented by notated musical settings for its chants transmitted in manuscripts ranging in date from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries. Manuscripts with archaic and intervallically imprecise forms of Byzantine musical signs (neumes) were consulted alongside the earliest available versions of Passion chants in the readily decipherable Middle Byzantine Notation, a system that was employed from the later twelfth century until the notational reform by the ‘Three Teachers’ (Chrysanthos of Madytos, Chourmouzios the Archivist, and Gregorios the Protopsaltes) first introduced in 1814. Dr Ioannis Arvanitis, a leading authority on medieval Byzantine musical rhythm and performance practice, then edited and transcribed the chants into the Chrysanthine ‘New Method’ of Byzantine notation for use by the singers of Cappella Romana.

The present recording features excerpts from the Service of the Holy Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ as it would have been celebrated in Jerusalem during the transitional period of its ritual Byzantinisation. An archaic cousin of the service celebrated in the modern Byzantine rite on Holy Thursday evening, this is a stational version of the office of early morning prayer (matins or orthros, literally ‘dawn’) in which eleven gospel readings narrate the events of the Passion of Jesus in a sequence beginning with his Last Discourse to his disciples (John 13:31–18:1) and ending with his burial (John 19:38–42). The texts and rubrics of the Typikon of the Anastasis form the basis of our reconstruction, supplemented by notated musical settings for its chants transmitted in manuscripts ranging in date from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries. Manuscripts with archaic and intervallically imprecise forms of Byzantine musical signs (neumes) were consulted alongside the earliest available versions of Passion chants in the readily decipherable Middle Byzantine Notation, a system that was employed from the later twelfth century until the notational reform by the ‘Three Teachers’ (Chrysanthos of Madytos, Chourmouzios the Archivist, and Gregorios the Protopsaltes) first introduced in 1814. Dr Ioannis Arvanitis, a leading authority on medieval Byzantine musical rhythm and performance practice, then edited and transcribed the chants into the Chrysanthine ‘New Method’ of Byzantine notation for use by the singers of Cappella Romana.

You must be logged in to post a comment.