Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377)

Guillaume de Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame (c. 1360-65) began to attract great interest during the 20th century. It is the first mass composed for four voices with a known composer, and as such, it is widely considered to mark the beginning of a new musical era. In addition, Machaut himself continues to fascinate many scholars. Not only a great singer, he was also a famous poet and diplomat who lived at the center of the social and political movements of his time. He spent half of his life as the secretary of King John of Bohemia, Duke of Luxemburg, with whom he traveled to nearly every country in Europe.

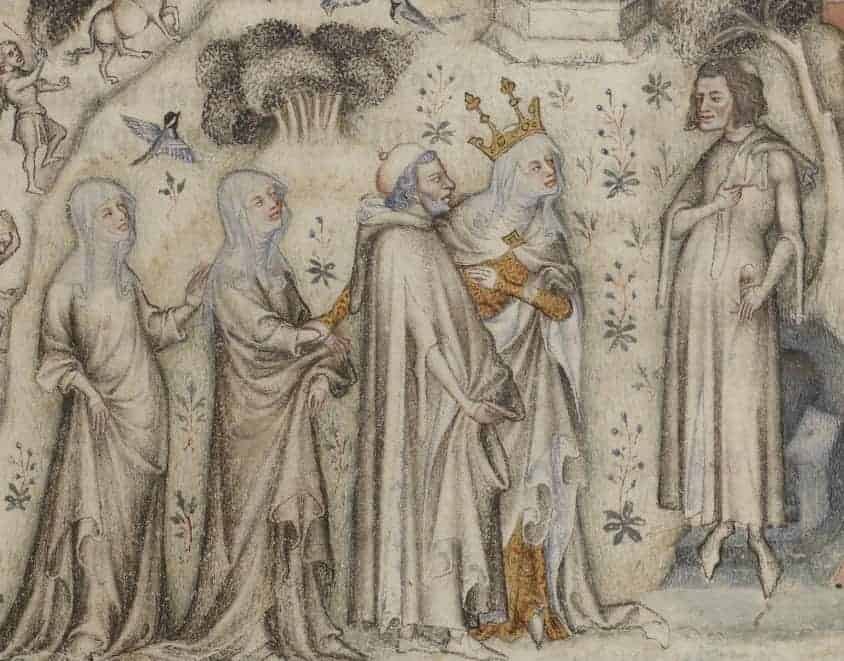

The movement of the papacy to Avignon in 1309 prompted a migratory movement of singers from the north who disseminated their art and built connections with their southern counterparts from Aquitaine, Quercy, Catalonia, and Italy. Musicians who had once been attached to a specific location now began to travel from cathedrals to princely courts, to learn and to offer their skills. Their circulation created an unprecedented exchange of musical techniques, and the style of Machaut’s Mass is a testament to this cosmopolitan collaboration.

Machaut was also a priest and canon, even though the majority of his work dealt primarily with romantic rather than sacred subjects. He composed the Messe de Nostre Dame toward the end of his life, but it is interesting to note that at the same time he also wrote another masterpiece, Le voir dit, a setting of his poem describing courtly love.

Gothic Art?

Artists of the 14th century would have been astonished and perhaps affronted to hear their creations described as “Gothic.” The word only came into use beginning in the 16th century to designate the aesthetic of the previous three centuries, which was considered somewhat barbarous by those who saw Antiquity as the archetype for all art. They no longer shared the world-view that gave birth to the artistic forms of the preceding centuries, which 19th-century historians later categorized once and for all as “Gothic.” Today, for the sake of convenience, we continue to use this word for the period, conscious that neither the Goths nor the European people of the late Middle Ages had the slightest idea that historians would lump them together under a single term.

Artists of the 14th century would have been astonished and perhaps affronted to hear their creations described as “Gothic.” The word only came into use beginning in the 16th century to designate the aesthetic of the previous three centuries, which was considered somewhat barbarous by those who saw Antiquity as the archetype for all art. They no longer shared the world-view that gave birth to the artistic forms of the preceding centuries, which 19th-century historians later categorized once and for all as “Gothic.” Today, for the sake of convenience, we continue to use this word for the period, conscious that neither the Goths nor the European people of the late Middle Ages had the slightest idea that historians would lump them together under a single term.

During the Gothic period, Europeans saw themselves as profoundly modern and uniquely able, thanks to the development of their faculties of observation and analysis, to utilize the laws of nature to create architectural or mental constructs that had hitherto been impossible. This period is largely the result of a tremendous enthusiasm that swept through the consciousness of the time, giving rise to new forms that synthesized age-old skills and recently mastered techniques, the fruits of observation and the spirit of analysis; in a word, science. The creators of the time, particularly the musicians among them, considered themselves deeply scientific, an adjective that today seems anachronistic, but which accurately sums up their self-image.

A Musical Revolution

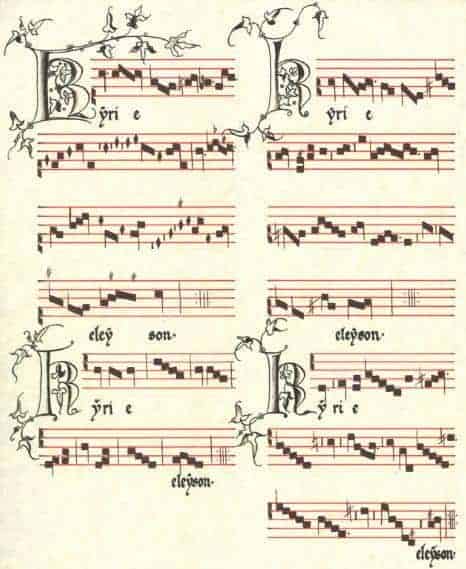

In the 13th century, music underwent a radical evolution, both in theory and practice. A new musical notation system made it possible for the first time to indicate the precise duration of sounds. This was the result of efforts begun in the Carolingian period to forge tools that would enable composers to notate their music with increasing precision. Music manuscripts of the 9th and 10th centuries indicate only the articulation and ornamentation of the melody, since a system for analyzing and notating intervals was not developed until the early 11th century. In the late 13th century, musicians finally succeeded in devising a notation that also indicated every possible note-length.

In the 13th century, music underwent a radical evolution, both in theory and practice. A new musical notation system made it possible for the first time to indicate the precise duration of sounds. This was the result of efforts begun in the Carolingian period to forge tools that would enable composers to notate their music with increasing precision. Music manuscripts of the 9th and 10th centuries indicate only the articulation and ornamentation of the melody, since a system for analyzing and notating intervals was not developed until the early 11th century. In the late 13th century, musicians finally succeeded in devising a notation that also indicated every possible note-length.

When these new models of notation were proposed, they began to radically alter our relationship with time. Music, a phenomenon that could previously be properly grasped only through action, became an object of contemplation. Its unfolding in time could be perceived as a mathematical or geometrical object, independent of its manifestation in sound. This “freezing” of sound made it possible to scrutinize and structure the deployment of the sound material, creating a temporal object outside of time.

Musicians embraced this concept eagerly, and toward the middle of the 14th century an even more complex and sophisticated movement, later known as the Ars Subtilior, began to explore the temporal combinations that notation permitted to their furthest extreme. A far-reaching transformation took place. The mastery of numbers in the sphere of time gave men the impression that they had become something greater than mere cogs in a greater cosmic order. Thanks to the mathematical mastery of durations, music had become geometry of time.

With this new ability to conceive music outside of time, musicians began to regard themselves as creators, building structures that did not exist before their intervention in the sound material. This is probably why the 14th century gave rise to the gradual emergence of named composers.

Polyphony, Chant, and Performance

To set these colorful polyphonic pieces in their ritual context, we have surrounded the mass with some Gregorian chants sung in the French manner described by Jerome of Moravia in the late 13th century. These are the Propers of the Mass of the Purification of the Virgin. The tempo of plainchant expresses the degree of solemnity. It is brisk and lively on ordinary days, while the rhythm of declamation was slowed down for great liturgical celebrations. Polyphony always appears in a context of solemnity, for it permits one to sing the words even more slowly. This is why it was sometimes called the Positio Solemnis (“Solemn Position”). The slower the chant, the more space opens up for the art of ornamentation to blossom. Today – despite the evidence of documents of the period – performers who attempt to recreate this music of the 14th century have a tendency to ignore this art. This is a pity, because the practice, far from being a superfluous element, constitutes the very basis of the art of chant. Ornamentation conveys the skill, and therefore the legitimacy, of the singer. Ornaments are above all at the service of the text, bringing out the subtlety of its phrasing. It attracts the listeners’ attention to the complex sounds of the words by underlining syllabic articulations: the diphthongs, liquescences, and percussiveness of certain consonants that are important for the understanding of the word. The art of ornamentation, when properly mastered, opens the listeners’ minds to multiple resonances of the text which is uttered, for each word is polished, sculpted like a precious stone in which every cut, by reflecting the rays it receives, projects the twinkling of light.

– Marcel Pérès

Machaut: Messe de Nostre Dame Tickets

SEATTLE

Fri 2 Feb, 8:00pm

St. James Cathedral

TICKETS

Add to Calendar

PORTLAND

Sat 3 Feb, 8:00pm

St. Mary’s Cathedral

TICKETS

Add to Calendar

EUGENE

Sun 4 Feb, 3:00pm

Central Lutheran Church

TICKETS

FREE CONCERT co-sponsored by the OHC’s Endowment for Public Outreach in the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities.

You must be logged in to post a comment.