The genesis of this concert program occurred last season in January 2017 after renowned Finnish choral conductor Timo Nuoranne was slated to appear with Cappella Romana to direct Einojuhani Rautavaara’s Vigilia (All-Night Vigil). Timo Nuoranne has championed that work in particular throughout his career, having performed it with both Finnish and non-Finnish choirs, and made the definitive recording of the work with the Finnish Radio Chamber Choir in 1998 for the label Ondine.

Even after a series of unexpected delays at the Department of Homeland Security and the chaos that ensued after the presidential inauguration at the State Department (including its worldwide network of embassies), we took the risk and paid for Nuoranne’s flight changes three times. However, Nuoranne’s artist visa was only issued on the day of the first concert. Alas it was not to be, and patrons will recall that our associate music director John Michael Boyer stepped in to direct the program at the last minute.

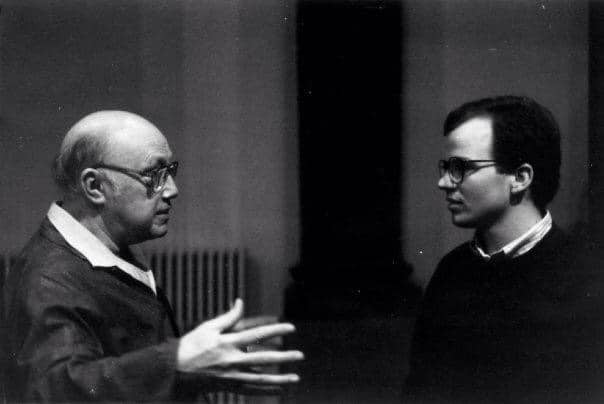

Shortly after the Vigilia performances we began to consider developing a new program that would suit Mr. Nuoranne’s considerable and broad expertise in Finno-Nordic sacred a cappella works from the last hundred years, virtuoso works “bathed in Arctic Light.”

As Timo and I began putting lists together of possible works to include, Cyrillus Kreek’s Psalm settings quickly rose to the top. In the 1980s as a young man Timo once sang Kreek’s Psalms in Finland under the direction of one of Estonia’s leading choral directors, Tõnu Kaljuste, who told the choir that a public performance of these Psalms would not have been possible in his own country at that time. Now Kreek’s music has the chance of being recognized as an important contribution to the choral canon alongside that of fellow Estonians Veljo Tormis and Arvo Pärt.

As Timo and I began putting lists together of possible works to include, Cyrillus Kreek’s Psalm settings quickly rose to the top. In the 1980s as a young man Timo once sang Kreek’s Psalms in Finland under the direction of one of Estonia’s leading choral directors, Tõnu Kaljuste, who told the choir that a public performance of these Psalms would not have been possible in his own country at that time. Now Kreek’s music has the chance of being recognized as an important contribution to the choral canon alongside that of fellow Estonians Veljo Tormis and Arvo Pärt.

Kreek’s Psalms take pride of place throughout this program for another reason: Cyrillus Kreek was an Orthodox Christian. His family converted from the Lutheran faith in 1896, with the young seven-year-old Karl taking on a new Slavicized name, Cyrillus. It’s curious that in the published edition of the Psalms there is no mention of this fact, perhaps in order to allow all Estonians (not only Orthodox) to lay claim to him as one of “their” composers. The editorial note in the score also makes no mention that the Psalms here are presented in forms regularly used in Orthodox services, including Orthodox liturgical refrains (not included in the Psalms themselves) that are also omitted in the score’s printed English and German translations.

Tickets

SEATTLE

Fri 17 Nov, 8:00pm

St. James Cathedral

TICKETS

Add to Calendar

PORTLAND

Sat 18 Nov, 8:00pm

St. Mary’s Cathedral

TICKETS

Add to Calendar

LAKE OSWEGO

Sun 19 Nov, 3:00pm

Marylhurst University

TICKETS

Add to Calendar

Our program follows at first a reasonably liturgical order. The first three Psalms on the program are those regularly sung at Orthodox Vespers, following the common Slavic tradition to excerpt select verses rather than sing the entire Psalm. The opening psalm of vespers 103 (104 in the Masoretic numbering) has an unmistakable folk feeling.

The second selection, Blessed is the Man, takes its title from Psalm 1:1, and is followed by verses from Psalms 2 and 3, forming the traditional first “Kathisma” from Saturday Vespers. Also featuring held pedal points that indicate a folk style, this setting uses the traditional Orthodox refrain “Alleluia” after each verse, with imitation of the refrain’s original melody cleverly imbedded into the music for the verses.

The lamplighting psalms at Orthodox vespers open with the first two verses of 140 (141 Mas.). In this setting, Kreek follows the ancient (and contemporary Slavic) tradition of refrains after the verses “Hear me O Lord” (“Kuule mind oh Issand”). After the male choir takes the second verse in four-part harmony, Kreek adds additional imperative versions of the refrain “Hear me, hear me, hear me,” that give the music a personal as well as corporate tone.

These three Psalms (along with Psalm 121/120 not included on this program) were completed in 1923, at the time the Estonian Orthodox Church had cut ties with the Moscow Patriarchate following the Russian revolution, aligning itself instead with the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which allowed more use of Estonian in Orthodox services. This remains the case to this day in the contemporary Apostolic Orthodox Church of Estonia.

Since Psalm 140 is normally troped with hymns proper to the season, we have opted to insert a festal hymn from the Latin tradition, Danish composer Per Nørgård’s setting of two stanzas from a Marian hymn for Advent “Flos ut rosa floruit.” Nørgård’s most celebrated choral work is the infamous Wie ein Kind (“Like a child”) from 1980 with texts by the schizophrenic Swiss artist Adolf Wölfli and Rainer Maria Rilke. Unlike the outbursts of Wie ein Kind this short motet gracefully floats along in a rocking motion, somehow in sync with the beating of the human heart. The stanzas of the hymn end with the refrain “nova genitura” undulating in C major, but ending unresolved on G, a non-foundational note of the chord, perhaps implying that the “nova genitura” (“new birth”) is ongoing.

Following Psalm 140 in Orthodox vespers the clergy prepare to enter the sanctuary again following the singing of “O Joyful Light” (Phos hilaron), which in its Finnish translation begins with “O Jesus Christ.” In this setting by Boris Jakubov (a Finn with Slavic roots), the composer shows an inventive, restrained treatment of the text, only gradually increasing the range and dynamic of the music for a fitting, noble conclusion. Jakubov studied at the Helsinki Music Academy and worked for a while at an Orthodox seminary in an area of Karelia that was part of Finland from 1812 to 1940.

In an historic Latin-rite mass the readings and psalmody, including the Alleluia, were followed by a sequence on high days. In medieval Denmark, one such sequence was “Gaudet mater ecclesia,” which was sung in honor of St. Knud Lavards (canonized in 1170). Unlike “Flos ut rosa floruit,” this setting is based on the text’s traditional chant melody, punctuated between the stanzas with a series of bell effects on the word “gaudet” (“rejoice”).

In the place of scripture readings, we present instead a setting of New Testament verses for Advent by Swedish composer Sven-Erik Bäck. Bäck pushes the limits of an a cappella choir in his motet Natten är framskriden, assuming that the singers can, without an instrument giving fixed pitch references, master sudden shifts in tonality in unrelated keys for expressive effect. Just as an expressionist painter distorts representation for emotional effect, here Bäck distorts conventional tonality to create distinct, shifting feelings in each word or phrase. At times both a major and minor version of a chord or melody is heard simultaneously, and melodies can display wide displacements of more than an octave. In the opening section “the day is almost here” (“och dagen är nära”), the cadence almost arrives at F-sharp major, but in first inversion with a minor third in the bass further keeping it from resolution. Bäck was not only a musician but also a theologian by training, and his sacred motets display a keen attention to a text’s exegesis through musical devices. At the close of the motet, the music moves to the distant key of C, in both major and minor, finally resolving to major but again in first inversion, leaving the listener in state of anticipation: indeed Christmas Day is coming, but not yet here.

Incidentally Bäck was one of the early collaborators of Eric Ericson (1918–2013), the greatest choral leader in modern Sweden, who with the Swedish Radio Choir that he founded in 1951 aimed to elevate choral singers to the level of orchestral players, not only in terms of pay and working conditions, but especially of uncompromising musical skill and virtuosity. Some of that virtuosity was on display when Ericson came to Portland in 1983 to direct a regional collegiate choir, which made a big impact on me as an impressionable 15-year-old in the audience. Later in my 20s I had the opportunity to sing under his direction some of the same music on this program in the Choeur de Chambre de Namur in Belgium, fulfilling a young singer’s dream of working with him and extending my artistic formation with northern exposure.

Nørgård’s Agnus Dei sets only the last section of the ordinary text with the appeal for peace (“dona nobis pacem”). Following a dramatic opening on its first vowel, a melody appears first in the tenor, then in the alto, then is transformed and agitated until “dona nobis pacem.” Like Bäck’s Advent motet, this one ends unresolved: on a major-seventh sonority without a root, seeming to question if true peace is attainable, at least in this life.

These modern composers are not the only ones to explore the outer limits of harmonic possibilities. Kreek’s 1914 psalm settings recall music by Strauss or early Schoenberg with constant shifting tone centers. His Psalm 84 (83 LXX), along with Psalm 22, are harmonically more experimental than the later 1923 collection, moving quickly through a variety of key centers from the outset and returning home only at the close. Psalm 84 invokes a medieval style undulating melody sung in parallel fourths (at “my soul longs”), while Psalm 22’s text receives dramatically shifting melodies in distant keys before returning to a C sonority without a third, leaving its tonality ambiguous as Kreek again appends a personal imperative “Deliver my soul, my own soul alone.”

Program List

??NORWAY

Edvard GRIEG: Fire salmer (Four hymns) 1, 2, 4

Knut NYSTEDT: Veni sancte spiritus

??SWEDEN

Sven-Erik BÄCK: Natten är framskriden

Thomas JENNEFELT: O Domine

??DENMARK

Per NØRGÅRD: Agnus Dei, Gaudet mater, Flos ut rosa floruit

??FINLAND

Pekka ATTINEN: Saata, oi Kristus

Boris JAKUBOV: Ehtooveisu

??ESTONIA

Cyrillus KREEK: Psalms

Knut Nystedt’s Veni was written in 1979, treating this impeccable sacred Latin poem with dramatic effects, especially antiphonal female and male choirs each answering the other in unrelated keys simultaneously, creating colorful sonorities that match the poem’s evocative images. Like Eric Ericson, Nystedt also founded a virtuoso ensemble, the Norwegian Soloists’ Choir in 1950, which he conducted for forty years and through it advocated for increasingly higher skills in a cappella singing. Perhaps second only to his Immortal Bach, Veni is one of his best-known pieces. Nystedt was beloved by many and passed away in 2014 just shy of his 100th birthday.

If it weren’t for its use of an Estonian rather than a Slavonic text, it would be difficult to tell if Kreek’s setting of Psalm 136 (137 Mas.) weren’t by one of the Russian New School of composers such as Rachmaninoff or Gretchaninoff. Kreek was a student of composition at the St. Petersburg Conservatory when one of his teachers would have been Maximilian Steinberg, student and son-in-law of Rimsky-Korsakov and composer of the now celebrated Passion Week, of which Cappella Romana gave the world premiere performances and world premiere recording in 2014. Rather prominent echoes of Steinberg’s compositional voice from Passion Week can be heard in Kreek’s setting here from 1944. From 1942 to 1944 the Estonian Orthodox Church was granted a short period of autonomy, followed by a dramatic exile of clergy and many faithful to Sweden during the second Soviet occupation, lasting from 1944 until Estonian independence in 1991. Kreek remained in Estonia however for the rest of his life.

Thomas Jennefelt’s O Domine stands as one of the most famous works of the modern Swedish school of a cappella choral music. Using fragments of the Requiem mass text, the piece opens with angular outbursts from choir and mezzo-soprano soloist, a discongruous collage of wildly expressionistic effects: speaking chorus, tone clusters, complex mechanical rhythms, and highly dissonant chords sung first in one octave then the next in quick succession: a technical tour-de-force for even the best of choirs. The piece ends with “In paradisum” during which the choir sings the syllables of the text with as little accentuation as possible, all becoming clear and full of consolation. As silence becomes part of the composition, the listener is left with the impression that the singing is still going on by the angels, in paradise.

Following this somewhat postmodern treatment of the Requiem texts, we follow it with a more solid hymn of comfort for the living, the Kontakion of the Dead from the Orthodox memorial service. This setting in Finnish by Pekka Attinen begins conventionally but opens up with transcendent sonorities on the words “life everlasting.”

Edvard Grieg’s Four Hymns (Fire Salmer) were the Norwegian composer’s last compositions, written in 1906 less than a year before he died. Cappella Romana will perform three of them in this concert (with soloists who incidentally each come from Norwegian heritage!). The first treats a paraphrase of the Song of Songs in a highly personal way, reflecting a kind of Lutheran-style piety with an emphasis on personal devotion and individual connection to Jesus Christ. Likewise in the second hymn the text emphasizes the salvific act of Jesus Christ on the individual believer, with the final hymn granting the individual Christian a glimpse of heaven. While Grieg once had a desire to become a Lutheran pastor, he was known to have been ambivalent about religion throughout his life. However these songs are a testament to a deeply personal reflection on life and death. The tension between this world and the next is most expressed musically in the second hymn, in which the soloist sings in B-flat major, while the choir sings in B-flat minor. This technical feat is all the more remarkable given Grieg’s failing health; these are not among his parlor pieces.

He wrote in his diary at the time, “These small works are the only thing my wretched health has allowed me… The feeling ‘I could, but I cannot’ is heartbreaking. In vain I am fighting against a superior force and soon, I suppose, I shall have to give up completely.” Despite his sense of imminent death, the hymns reveal, through Grieg’s optimistic musical declamation and resolve, a sanguine hope and confident faith.

—Mark Powell, Executive Director, Cappella Romana

You must be logged in to post a comment.